|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

AZFO FIELD EXPEDITION

Galiuro Mountains

May 1-3, 2015

By Eric Hough

The famed ‘sky island’ mountain ranges of southeastern Arizona have received most of the birding and ornithological attention in the state, yet there are still some of these mountains that we surprisingly know very little about in terms of the avifauna that occur there. Lying between the lower San Pedro River Valley and the northern Sulphur Springs Valley, the Galiuro Mountains of southwestern Graham County are one of these seldom-visited ‘sky islands’. Much of the range lies within the 76,317-acre Galiuro Mountains Wilderness Area in the Coronado National Forest, managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Additionally, the mountains are bookended by two other U.S. Bureau of Land Management wilderness areas, Aravaipa and Redfield Canyons. Canyons draining the southern end of the mountains flow south through The Nature Conservancy’s Muleshoe Ranch Preserve. Much of the surrounding valleys and foothills outside of the wilderness areas and national forest land are privately-owned, restricting access points to certain roads where ranchers have allowed access through their land to reach designated trailheads leading up into the mountains. There are no forest roads going up into the mountains beyond these foothill trailheads though due to the remoteness of the steep, rugged terrain, leaving visitors to rely on hiking and/or pack animals to explore the higher reaches of these mountains.

Luckily, designated trails have been constructed throughout the mountains that are periodically maintained. However, the Galiuros lack perennial water in its canyons with only widely-scattered springs, which complicates backpacking trips. This ruggedness and scarcity of water has always been a deterrent to visitors, as evidenced by the scant historical records regarding these mountains. There is little evidence of prehistoric use by Native American groups, with visitors over the last two centuries comprised mostly of prospectors, ranchers, hunters, backpackers, geologists, and a few lawmen involved in an infamous shootout with a local ranching/mining family that led to the largest manhunt in state history (The Forest History Society 2008). Altogether, these challenges that have discouraged potential human visitation over the centuries are why much is still unknown about the bird life that inhabits this mountain range.

|

Figure 1. View from East Divide of the Galiuro Mountains looking west towards the Santa Catalina and Rincon Mountains (© Eric Hough).

|

The Galiuro Mountains are one of the lower-elevation ‘sky islands’ compared to nearby ranges, the elevations ranging from about 4,000 ft. in the foothills to the 7,671-ft. summit of Bassett Peak. The mountains are divided into two major ridges, the East and West Divides, which lie mostly within the 6,600-7,300 ft. elevation range. These two parallel ridgelines are divided by broad canyon valleys in Rattlesnake and Redfield Canyons. Along this elevation gradient, vegetation life zones cover upper Sonoran desert-scrub on the western base of the mountains, mid-elevation Chihuahuan Desert grasslands along the northern edge of the Sulphur Springs Valley along the eastern base of the mountains, and chaparral, pinyon-juniper-oak woodlands, pine-oak and mixed-conifer forests, and disjunct patches of aspens continuing up the mountain slopes. Common plant species encountered in the mountains include Arizona white oak (Quercus arizonica), Emory oak (Q. emoryi), silverleaf oak (Q. hypoleucoides), scrub-oak (Q. turbinella), netleaf oak (Q. rugosa), Gambel oak (Q. gambelii), ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), border pinyon pine (P. discolor), alligator juniper (Juniperus deppeana), Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), southwestern chokecherry (Prunus virginiana), New Mexico locust (Robinia neomexicana), manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.), and mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus spp.), with fewer numbers of Chihuahua pine (P. leiophylla), Arizona madrone (Arbutus arizonica), and quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). Despite the scarcity of surface water in the Galiuros, its canyons do have lush riparian vegetation dominated by bigtooth maple (Acer grandidentatum), boxelder (Acer negundo), velvet ash (Fraxinus velutina), Arizona walnut (Juglans major), and Arizona sycamore (Platanus wrightii).

|

|

|

Figure 2. View of Paddy’s River Canyon from East Divide (© Eric Hough). |

Figure 3. View eastern Galiuro Mountains from northern edge of Sulphur Springs Valley (© Eric Hough). |

While adjacent Aravaipa Canyon at the northern periphery of the range and Muleshoe Ranch Preserve south of the mountains are occasionally visited by birders, very little is still known about the bird distribution of the entire Galiuro Mountains. Searching through hotspots and species maps on the global eBird database (ebird.org) revealed a complete lack of data for the Galiuros. A search through peer-reviewed scientific literature yields mostly articles on the mountains’ volcanic geologic origins, with only a couple of articles regarding birds (or other wildlife for that matter): an article mentioning historic reports of wandering Thick-billed Parrot flocks in the Galiuro Mountains (Wetmore 1935) and another article discussing survival rates of ‘Gould’s’ Wild Turkeys transplanted from Yécora, Sonora (Mexico) to the Galiuro Mountains in 1994 and 1997 (Wakeling 1998). Even the primary Arizona ornithological texts outlining the status and distribution of the state’s birds list few species for the Galiuros (Phillips et al. 1964, Monson & Phillips 1981). While some surveyors for the Arizona Breeding Bird Atlas and Spotted Owl monitoring projects did venture into the Galiuro Mountains in the 1990s, the Atlas specifically mentions several species that have not been documented yet for this range, but that were thought to potentially occur based on their occurrence in nearby mountain ranges and the seemingly appropriate habitat for those species present in the Galiuros (Corman & Wise-Gervais 2005). A couple of new breeding species that the Atlas surveys detected in the Galiuros included Whiskered Screech-Owl and Arizona Woodpecker, these mountains marking the northernmost limit for the owl’s entire species range and these mountains being a new range for the woodpeckers where they had only been detected once before in winter on the southern slopes (Phillips et al. 1964, Corman & Wise-Gervais 2005). The only recent bird report from here prior to our expedition was the exciting discovery of two Elegant Trogons photographed in Rattlesnake Canyon on the north side of the mountains on April 17-18, 2011, by Arizona Game & Fish Department herpetologists conducting Chiricahua leopard frog surveys (Arizona Field Ornithologists 2011).

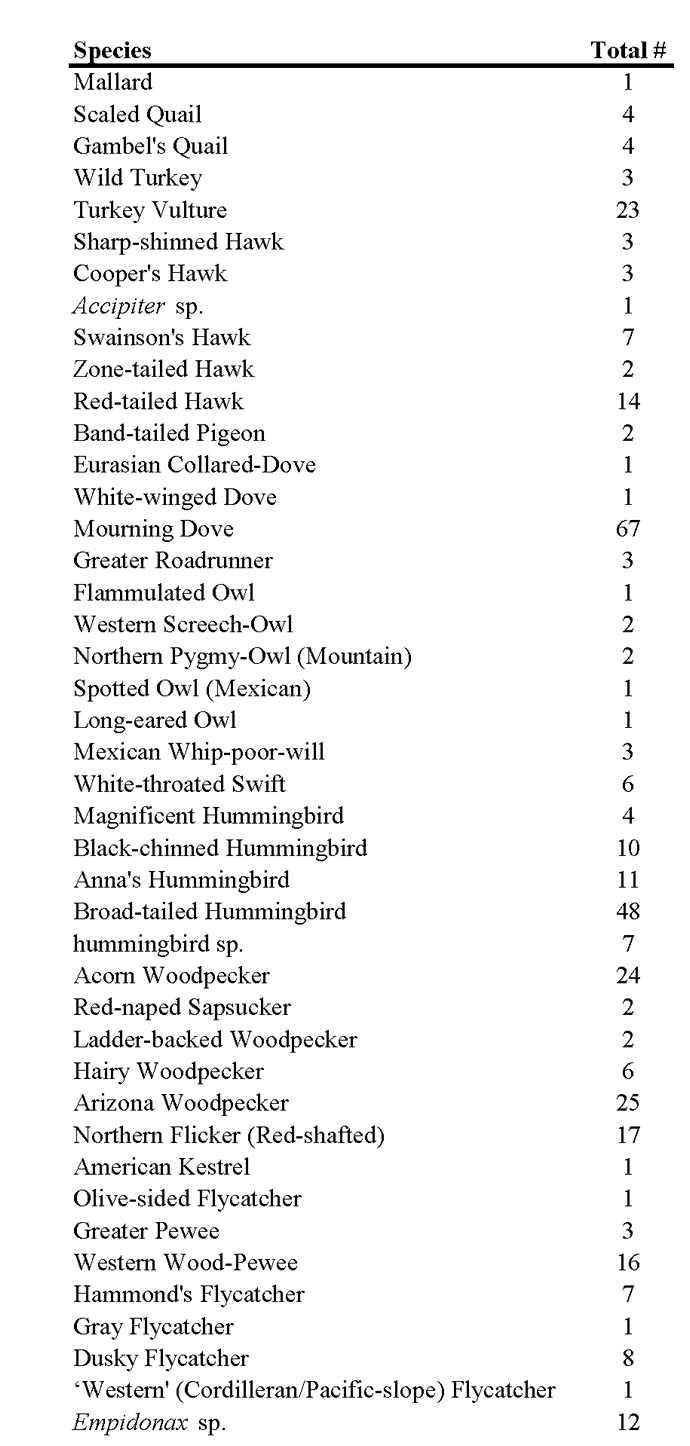

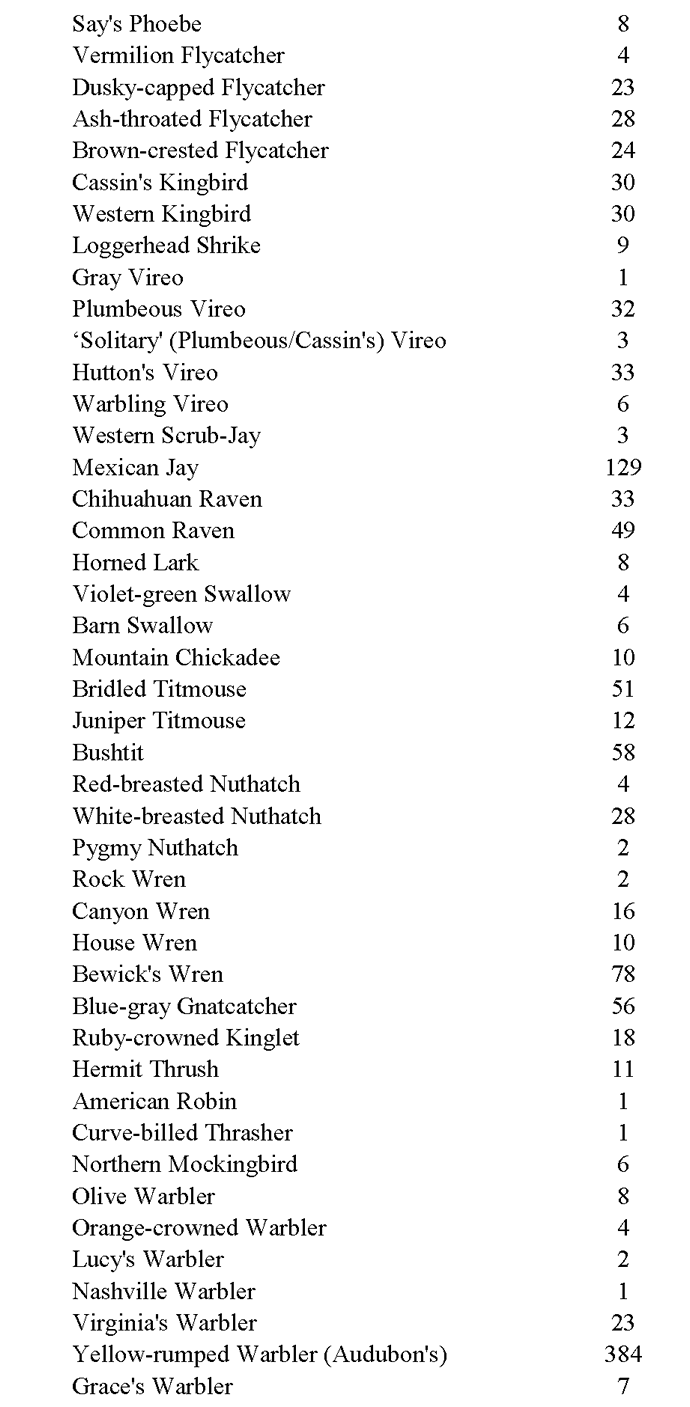

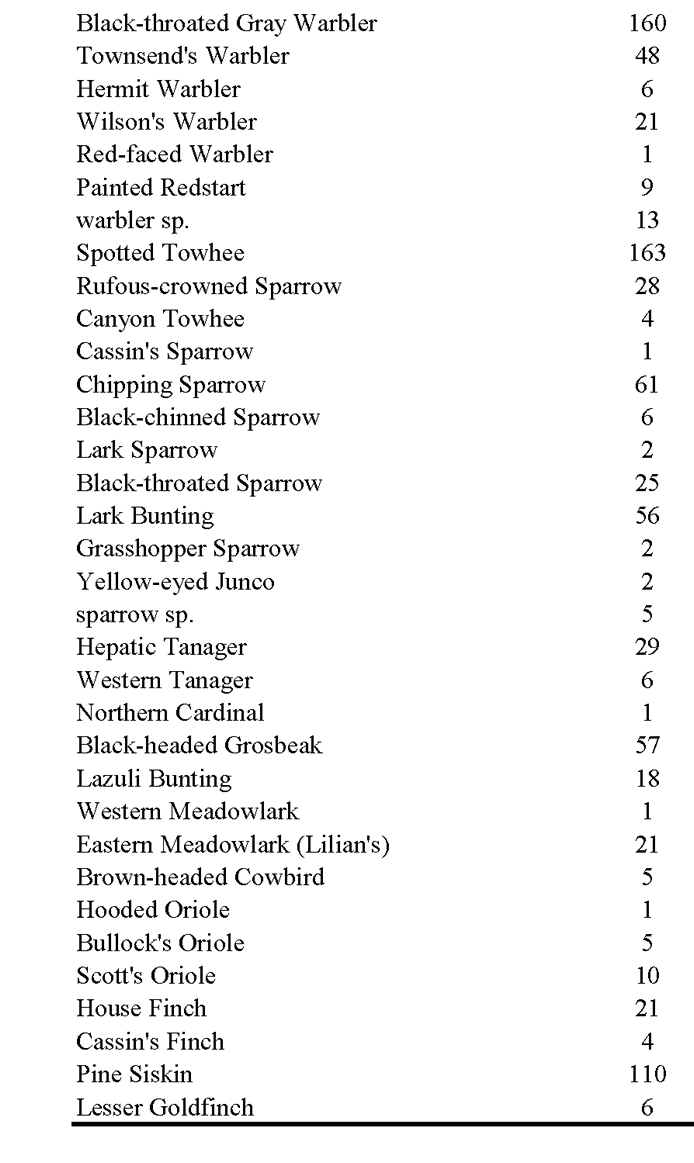

For this AZFO expedition, five intrepid participants formed two teams to backpack and day-hike into the Galiuro Mountains on May 1-3, 2015, to document the avifauna of these mountains and see if previously undetected species could be found. Total species numbers for this expedition are shown in Table 1 of the Appendix, adjusted to account for the same stretches of trail being covered on return hikes to avoid counting the same individuals twice in the data; in these instances the highest number of a species recorded at the same location during different observation periods was taken to represent the minimum number of each species present along these stretches of trail.

|

Figure 4. Map of Galiuro Mountains and surrounding area (© Google Earth 2015). |

Northern Sulphur Springs Valley / Eastern Foothills

On May 1st our group convened in Willcox to caravan up to the eastern side of the Galiuro Mountains via Fort Grant Rd., Ash Creek Rd. (Forest Rd. 651), and High Creek Rd. (Forest Rds. 159/693/693A). This approach starts out going by agricultural fields, then going through grassland and desert-scrub habitat. Along the way we saw a few Scaled Quail, a flock of ~50 Lark Buntings, heard several Eastern ‘Lilian’s’ Meadowlarks, and saw small flocks of Chihuahuan Ravens. Once the road began paralleling riparian vegetation along creeks, we also encountered Gambel’s Quail, nesting Red-tailed and Swainson’s Hawks, Vermilion Flycatchers, Cassin’s and Western Kingbirds, Canyon Towhees, a Northern Cardinal, and Bullock’s Orioles. Turning onto a spur road that continues through the Coronado National Forest boundary continuing up towards Ash Creek Trailhead, the habitat turns from rolling grasslands into evergreen oak woodlands. Here we saw Acorn Woodpeckers, Mexican Jays, Black-throated Gray Warblers, and large migrant flocks of Yellow-rumped Warblers and Chipping Sparrows. At this point, our group split into two teams, with John Barthelme, Nathan Williams, and Sarah MacLean heading up Ash Creek, and Marceline VandeWater and myself heading north to the High Creek Trailhead.

After covering more of Ash Creek on May 3rd, Nathan, Sarah, and John checked out more of this adjacent grassland habitat along the edge of the northern Sulphur Springs Valley. Along Sunset Loop Rd., which travels north of the Ash Creek Rd. to the High Creek Rd. junction, their team found a Cassin’s Sparrow and two singing Grasshopper Sparrows. During the Atlas surveys, Grasshopper Sparrows were not found this far north in the valley (Corman & Wise-Gervais 2005) and were only historically listed as occurring north to the Fort Grant-Bonita area at the northern terminus of the valley (Phillips et al. 1964). Their team also got good looks at a Western Meadowlark, which is a rare and local breeder in this region of the state, while Eastern Meadowlarks reach their highest densities here. Owing to this distribution, both teams encountered plentiful Eastern Meadowlarks singing throughout this stretch. Additionally, we picked up a few more Lark Buntings migrating through.

|

|

|

Figure 6. Red-tailed Hawk nest (© Nathan Williams). |

Figure 5. Grassland, desert-scrub, and oak woodland habitat along Ash Creek Rd. east of the Galiuro Mountains (© Eric Hough). |

Ash Creek

On the afternoon of May 1st after our group split up, their team hiked along about 1.4 miles of road from their camp to the Ash Creek Trailhead. On their hike they found a few species that had not been previously reported in the Galiuro Mountains: Anna’s Hummingbird, House Wren, and Red-faced Warbler. The latter seemed to be at a lower elevation than usual, so it may have still been migrating through. However, continued coverage of these drainages would likely find this species as a breeder in the Galiuros given the abundance of bigtooth maples and Gambel oaks in the mid-elevation riparian canyons. Other common species they detected included Arizona Woodpeckers, three Myiarchus flycatcher species (Dusky-capped, Ash-throated, and Brown-crested), Bridled and Juniper Titmice, and several Black-throated Gray Warblers. Migrants included Gray and Dusky Flycatchers, Warbling Vireos, Ruby-crowned Kinglets, and Townsend’s and Wilson’s Warblers. They then headed back down the road to camp where they watched a pair of Northern Flickers attending a nest. At dusk they heard some odd noises nearby, which turned out to be two Wild Turkeys roosting up in an oak tree. Shortly after dusk they heard and saw a Long-eared Owl, another likely first for the Galiuro Mountains. Throughout the night they heard at least nine Common Poorwills singing from the grassy hills and forest around them.

|

|

|

| Figure 7. a) Ash Creek Trail (© Nathan Williams) | and b) Spotted Owl (© Nathan Williams). |

The next day, May 2nd, their group headed back up to the Ash Creek Trailhead, encountering the same species as the previous afternoon. The lower stretch of Ash Creek goes through oak woodlands and chaparral, then up through patches of ponderosa pines, maples, and riparian trees. Along lower Ash Creek from the trailhead to where the trail goes above the creek (about 1.9 miles from the trailhead), their species highlights included Acorn Woodpeckers around several acorn granary trees, two late migrant Red-naped Sapsuckers, a Greater Pewee (another first for the Galiuros), 10 Townsend’s Warblers, three Painted Redstarts, and five Pine Siskins (another possible first for these mountains). The siskins might have been just irruptive migrants, but the pine and mixed conifer habitat in these mountains would seem suitable for potential breeding. Among the several common pine-oak species, they did see a Spotted Towhee pair with recently fledged young too.

The team then covered another one-mile stretch of trail along upper Ash Creek to where the trail turns and begins switch-backs up the base of Bassett Peak. The habitat along here gradually goes through more pine-oak and mixed conifer habitat, with lush groves of old-growth bigtooth maples along the creek and even a patch of large aspens. Their best bird along this stretch was a Spotted Owl perched up in one of the maples, providing them great looks from its roost. Other species included Band-tailed Pigeon (another apparent first for the Galiuro Mountains), a Red-breasted Nuthatch, Grace’s, Black-throated Gray, Townsend’s, and Wilson’s Warblers, two Painted Redstarts, Hepatic Tanagers, Black-headed Grosbeaks, and a Scott’s Oriole. A surprise along the hike occurred when Nathan almost stepped on an Arizona black rattlesnake (Crotalus cerberus), but luckily the three of them safely got to enjoy looks at this beautiful rattlesnake. Arizona black rattlesnakes are nearly endemic to Arizona and occur at higher elevations than most other rattlesnake species in the state, blending in well with the shaded forest floors of their habitat (Brennan & Holycross 2006). That night back at camp along lower Ash Creek they heard a couple of Western Screech-Owls along with a few Common Poorwills.

The following day, May 3rd, their team again covered the stretch of Ash Creek between their camp and the trailhead. Some new species that they detected included a female Magnificent Hummingbird (another first for the Galiuros) and a Gray Vireo. They also found evidence of breeding activity for several species, including a pair of Swainson’s Hawks copulating, Hutton’s Vireos and Blue-gray Gnatcatchers nest building, and a pair of Juniper Titmice carrying food for nestlings in a tree cavity.

|

Figure 8. a) View of Sunset Peak from High Creek Trail (© Eric Hough) |

|

and b) Dusky-capped Flycatcher (© Eric Hough). |

High Creek / East Divide

Heading north from the turn for Ash Creek Trailhead along Sunset Loop Rd., the road travels through more grasslands with great views of the east side of the Galiuro Mountains and the taller Pinaleño Mountains to the west. The road also passes through a few east-flowing drainages with oak woodlands and sparse riparian habitat, where we detected Ladder-backed Woodpeckers and Lucy’s Warblers, the latter a previously-unreported species for these mountains. High Creek Rd. then travels west through more grassland and oak woodland, eventually heading into tall, dense oak woodland as it gains elevation along High Creek. There are multiple pullouts along the road where one can park, which is handy since the condition of the road gradually deteriorates towards the unmarked trailhead. Marceline’s high-clearance, 4WD vehicle luckily made it up through some rocky creek crossings to a small pullout about 0.25-0.5 mile from the end of the road/trailhead.

After loading up our backpacking gear, we started tallying birds as we headed up the road towards the trailhead. Along this lower stretch of High Creek, the dense oak woodlands produced Arizona Woodpeckers, Dusky-capped and Ash-throated Flycatchers, Mexican Jays, Bridled Titmice, Black-throated Gray Warblers, Hepatic Tanagers, and Black-headed Grosbeaks. Interestingly along this first stretch of creek we saw small numbers of Arizona madrones mixed in with the oaks, which was farther north than we realized the species was distributed. Above the creek on the chaparral hillsides we heard Bushtits, Bewick’s Wrens, Blue-gray Gnatcatchers, Virginia’s Warblers, Spotted Towhees, Rufous-crowned and Black-chinned Sparrows. The creek bed had trickling water and a few pools on this lower stretch, but quickly disappeared as we continued up the trail. Perhaps owing to this short stretch of available water, we encountered a male Hooded Oriole, which was another new species for the Galiuros and one we did not expect to detect this far up the canyon into the mountains. Gradually we began to see some ponderosa pines, Gambel oaks, and bigtooth maples appearing, along with an Anna’s Hummingbird, a few Western Wood-Pewees, a singing Hermit Thrush (another new species for these mountains), and a couple of Painted Redstarts. Occasional mixed passerine flocks were also present containing such species as Hammond’s Flycatchers and Townsend’s Warblers. The slow climb with our backpacking gear ended after some switchbacks above High Creek where the trail intersects the East Divide Trail, which travels north-south along most of the East Divide ridgeline of the mountains. From where we parked our vehicle at an elevation of 5,348 ft., we ascended 1,640 ft. in about two miles to an elevation of 6,772 ft. at the trail junction. From here we had great views to the southeast of the distant Dos Cabezas and Chiricahua Mountains, and the town of Willcox way out in the Sulphur Springs Valley where we had been earlier that morning.

From the High Creek Trail-East Divide Trail junction, we headed north along the East Divide for almost 0.2 mile to a saddle between the heads of the High Creek and Paddy’s River drainages, which both drain the eastern slope of the mountains. Here we found an old fire ring and a rusted, old mailbox attached to a wooden post, which presumably was used by either the U.S. Forest Service or local ranchers to communicate with each other when surveying these rugged mountains. The top of the mailbox was warped shut, so we were not able to peek inside. However, we were intrigued by rustling noises we heard inside the box, which ended up taking us until Sunday morning to determine the culprit of (more on that later). Arriving at this nice flat spot in the late afternoon, we decided to set up our camp here for the weekend. The elevation of this mailbox camp is at 6,988 ft., with ponderosa pines, Douglas-firs, some evergreen oak species, and alligator junipers comprising the habitat here. Not long after arriving we detected one of our sought-after species for the expedition, a singing male Yellow-eyed Junco. Nearby Mountain Chickadees, Pygmy Nuthatches, and a flyover American Robin were also new species for the Galiuro Mountains. We also enjoyed looks at a Dusky-capped Flycatcher and Grace’s Warbler, and heard a few Hermit Thrushes singing away as evening approached. After dusk, we heard the double-note tooting of a ‘Mountain’ Northern Pygmy-Owl (Glaucidium gnoma gnoma), the form that occurs in southeastern Arizona southward into Mexico. Shortly thereafter, three Mexican Whip-poor-wills began vigorously singing and fighting over territory boundaries.

|

Figure 9. Pine-oak forest with bigtooth maples along High Creek Trail (© Eric Hough). |

Before dawn the next morning we again heard the Northern Pygmy-Owl and one of the Mexican Whip-poor-wills, shifting into the dawn chorus of other species such as Dusky-capped and Ash-throated Flycatchers, Hutton’s Vireo, Mountain Chickadees, and Hermit Thrushes. The territorial Yellow-eyed Junco again made an appearance, as did a Hairy Woodpecker, yet another previously unrecorded species for these mountains. The real show began as the sun started to peek over the ridge above High Creek and a steady wave of migrant passerines began to work their way up and over the saddle from High Creek. Before the migrants continued along the East Divide, many stopped to forage in some of the Douglas-firs and ponderosa pines around our camp. We watched the spectacle for over an hour while we ate breakfast and got ready for our day hike, with highlights including two Orange-crowned, one Nashville, 200+ Yellow-rumped, six Townsend’s, three Hermit, and two Wilson’s Warblers, 12 Chipping Sparrows, a Western Tanager, 13 Lazuli Buntings, three Cassin’s Finches, and 82+ Pine Siskins. Most of the Pine Siskins were likely irruptive migrants from this past winter, although the habitat present in the Galiuro Mountains would seem to support possible breeding of this species, adding another new potential breeding resident for this range. We also heard the loud wing trill of at least six Broad-tailed Hummingbirds flying over, which may have been migrants or possibly breeders. A couple of resident Olive Warblers joined in with the mixed migrant flocks too.

|

|

|

Figure 10. a) Yellow-eyed Junco (© Eric Hough) and

|

Figure 10. b) Magnificent Hummingbird (c Eric Hough) |

Marceline and I then began our day hike along the East Divide Trail north of the mailbox camp, encountering another singing male Yellow-eyed Junco less than a quarter-mile beyond our camp. This was to be only the second individual of this species that we would detect during this expedition, suggesting that the population density of this species is very low in the Galiuro Mountains. We also saw a pair of Dusky-capped Flycatchers acting agitated around a snag with cavities, along with agitated pairs of Hutton’s Vireos and Blue-gray Gnatcatchers that were likely already tending nests. Initially the trail went through more pine-oak forests with a few stands of ponderosa pines, then through a mixture of oak-juniper-manzanita woodlands with scattered Douglas-firs. Down below us in the head of the Paddy’s River drainage we spotted a few Chihuahua pines, which we interestingly failed to encounter more of during the expedition. In one drainage with large Douglas-firs we heard a singing Red-breasted Nuthatch and more Mountain Chickadees.

|

Figure 11. Mixed conifer and pine-oak forest along East Divide Trail (© Eric Hough). |

As we neared a saddle on the East Divide that finally gave us a view over the western side of the Galiuros, we heard a raptor screaming below us to the east down in the Paddy’s River Canyon. We then witnessed a territorial dispute between two Zone-tailed Hawks. Throughout the day we saw one to two Zone-tailed Hawks flying over the East Divide, making us think at least one pair may have been nesting in the area. As we paused to rest and take in the breathtaking view from the high Galiuros, we watched a few Violet-green Swallows engaged in courtship displays. Among the rocks along the trail we spotted a couple of Yarrow’s spiny-lizards (Sceloporus jarrovii), a resident of the ‘sky islands’ of southeastern Arizona. Even with the partly cloudy skies, taking in the incredible view at this 7,236 ft. saddle we were able to pick out the Rincon, Santa Catalina, Pinal, Santa Teresa, Gila, Pinaleño, Dos Cabezas, Chiricahua, and Winchester Mountains, along with the San Pedro River, the town of Oracle, and even Picacho Peak way out past Oracle! Looking south of the saddle down the East Divide we had a clear view of Bassett Peak eight miles to the south, where the other team was making their way to the base of along Ash Creek. Just the sheer immensity of this view alone is worth a backpacking trip into the Galiuros.

|

Figure 12. View from East Divide looking south-southwest towards Bassett Peak (far left) and distant Whetstone, Rincon, and Santa Catalina Mountains (© Eric Hough). |

Not far past the saddle we came to the intersection of the East Divide and Rattlesnake Trails at 7,238 ft. Pausing at the trail junction, we noticed several scratch marks left by a black bear. All along the trails that we covered this weekend we saw dozens of scat piles left by black bears, suggesting higher use of these trails by this species than humans. We continued north on the East Divide which stays fairly flat traversing the pinyon-juniper and oak woodlands, manzanita thickets, and scattered Douglas-firs. This stretch of trail was inhabited by high numbers of Black-throated Gray Warblers and Spotted Towhees, in addition to several Anna’s and Broad-tailed Hummingbirds, a few Western Scrub-Jays, and Juniper Titmice also seen. Migrant flocks included more Yellow-rumped, Townsend’s, and Hermit Warblers, Chipping Sparrows, and an unexpected Western Kingbird.

Continuing north we saw a burn area in the distance over the northeastern portion of the mountains around Kennedy Peak. Looking up information on this burn following our expedition revealed that it was from the lightning-caused Oak Fire that occurred the previous year on June 17-July 7+, 2014, that burned 13,920+ acres (Inciweb 2014, Arizona Prescribed Fire Council 2014). The fire covered the northeastern quarter of the Galiuro Mountains primary east of Rattlesnake Canyon and north of Douglas Canyon and was a mosaic of burn severity across the landscape. The East Divide Trail traveled through one of the higher severity stretches of burn, subsequent erosion after the fire erasing the trail in a couple of places and forcing us to guess where the trail went. Lots of wildflowers were beginning to come up in the ash around the scorched tree trunks, including verbena (Verbena sp.) patches that painted the blackened hillsides with pink and purple. A surprise in the burn area was finding an owl’s clover (Castilleja exserta or Orthocarpus purpurascens), a species typically found in lower elevation deserts. Finding this plant above 7,000 ft. elevation made us think that the seed that bore this plant must have been in the seed mixture that the U.S. Forest Service dropped over the burn area to prevent erosion. In the burn area we saw a few Hairy and Arizona Woodpeckers taking advantage of the increased insect populations foraging on the dead timber. Down below us in the South Fork of Douglas Canyon we saw a large patch aspens, riparian, and mixed conifer vegetation, which would be another place worth investigating on a future AZFO expedition. Given the scarcity of aspens in the southeastern Arizona ‘sky islands’, it would be interesting to see which species are nesting in that habitat.

|

|

|

Figure 13. View from East Divide looking west-northwest towards distant Santa Catalina Mountains (© Eric Hough). |

Figure 14. Oak Fire burn area along East Divide looking west-southwest towards aspen and maple groves down in South Fork of Douglas Canyon (© Eric Hough).

|

We only had time to go along the trail to an upper stretch of the South Fork of Douglas Canyon before we had to turn back to head back to our camp before dark. This stretch of the canyon at 6,617 ft. was partially burned by the 2014 Oak Fire, but still contained stands of old growth Douglas-firs and ponderosa pines that survived the fire. In the short time we were able to spend in the canyon in the early afternoon we detected a singing Greater Pewee (another new species for these mountains), Hairy Woodpeckers, Dusky-capped Flycatchers, Mountain Chickadees, a Red-breasted Nuthatch, House Wrens, an Olive Warbler, a few Townsend’s Warblers, several Yellow-rumped Warblers, a Painted Redstart, and a Western Tanager.

Heading back down the East Divide to camp we detected similar species and were treated to cool breezes as some small storm clouds passed over. In the windy conditions, a few Red-tailed Hawks and Turkey Vultures soared above us and several Common Ravens did fancy aerial maneuvers while playing in the wind. Just before dusk back at the mailbox camp a male Magnificent Hummingbird briefly made an appearance, yet another new species for the mountains. After dusk the three singing Mexican Whip-poor-wills continued their territorial disputes and we heard a distant Flammulated Owl softly hooting.

Before dawn on May 3rd some light rain went through, but we lucked out with the weather for the rest of the day. On this morning we did not see the same migrant waves passing over the divide as we did the previous morning, but we did have some new detections at our camp including a calling Wild Turkey nearby, a flyover Band-tailed Pigeon (a new species for the mountains), a singing Greater Pewee, three male Magnificent Hummingbirds engaged in a territorial dispute, and a singing Scott’s Oriole. As we packed up our camp for the hike back down High Creek, we finally determined the source of noises that we had been hearing in the old mailbox at our camp: a family of super cute cliff chipmunks (Tamias dorsalis) that had made their nest inside.

|

|

|

| Figure 15. a) cliff chipmunks in old mailbox along East Divide Trail (© Eric Hough) | and b) Mexican Jay nestlings (© Eric Hough). |

Descending down into High Creek we encountered more migrant flocks including Townsend’s and Yellow-rumped Warblers, Lazuli Buntings, and Pine Siskins, plus more singing territorial breeders in the pine-oak forest. As small storm clouds passed over and briefly darkened the sky, a ‘Mountain’ Northern Pygmy-Owl began calling somewhere above us on the slope. Other highlights included vocal Acorn and Arizona Woodpeckers, an Olive-sided Flycatcher, a Cassin’s Kingbirds, a few Empidonax flycatcher species, a couple of Warbling Vireos, a few Olive Warblers and Painted Redstarts, and a Bullock’s Oriole. We observed breeding evidence for several common species, including one Mexican Jay nest in an Arizona white oak right along the trail that we discovered when the mother flushed off the nest, which contained four chicks. Arriving back at the vehicle we heard a bizarre vocalization, which turned out to be a singing Plumbeous Vireo that seemed to either be doing an alternate song phrase, or had damaged vocal cords.

|

| Figure 16. a) Arizona black rattlesnake (© Eric Hough) |

|

| and b) black-tailed rattlesnake (© Eric Hough). |

However, our most exciting widlife finds came in the non-avian variety. Heading back up the trail a short distance

when we thought we heard a possible Ovenbird singing along the creek (which we think now was just a MacGillivray’s Warbler), I paused to check my camera to see if the video with audio recording I obtained of the bird’s vocalizations was sufficient. While staring down at the viewfinder on my camera, I noticed something above and just in front of the camera coiled up on a hip-high fallen log: my lifer Arizona black rattlesnake! What added more excitement to this sighting was the realization that we had probably walked within a foot of the resting rattlesnake while skirting around another fallen log on the trail. Farther down the trail we paused to check out the birds, butterflies, and dragonflies visiting the small remnant pools of water in High Creek and Marceline spotted our second rattlesnake of the trip, a rather large and bright yellow black-tailed rattlesnake (Crotalus molossus). The snake was crossing the creek and slithered up the creek bank right by us, allowing for great extended views. We were amazed the previous couple of days in not coming across any rattlesnakes, only to see two different species on our last day on the hike out.

Conclusion

The net gain in knowledge from this weekend expedition was more than we anticipated, with our group of five documenting 114 species, at least 17 of which being potential breeding species that had previously never been reported for the Galiuro Mountains: Swainson’s Hawk, Band-tailed Pigeon, Long-eared Owl, Magnificent and Anna’s Hummingbirds, Greater Pewee, Mountain Chickadee, Pygmy Nuthatch, House Wren, Hermit Thrush, American Robin, Virginia’s, Lucy’s, and Red-faced Warblers, Yellow-eyed Junco, Hooded Oriole, and Pine Siskin. Additionally, we found migrant species, such as Townsend’s and Hermit Warblers, and Cassin’s Finch, which are likely newly reported species for this range. In the adjacent grasslands bordering the foothills of the Galiuros in the northern Sulphur Springs Valley, we also found historically-occurring Grasshopper Sparrows still occupying this area, along with Cassin’s Sparrows that were not found this far north during the Atlas surveys. Additionally, we found continued occurrence of the introduced ‘Gould’s’ Wild Turkeys in these mountains. Furthermore, our expedition submitted the first-ever bird lists into the eBird database and the first audio recordings in Xeno-Canto from the Galiuro Mountains. Total species numbers can be viewed in Table 1 of the Appendix at the end of this article.

Not long after this expedition on May 22-24, Nick Beauregard, a Spotted Owl surveyor with Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory, reported at least five Elegant Trogons from Rattlesnake and Pipestem Canyons in the northern Galiuro Mountains where they had only been reported once before. Following this observation, belated reports came in of Elegant Trogons in Oak Grove Canyon near Aravaipa Canyon from as far back as 15 years ago (fide Tom and Debbie Collazo) and more trogons photographed at the Aravaipa Canyon Preserve over the past five years (fide Mark Haberstich). These reports expand the northernmost breeding range of this species to Aravaipa Canyon and the northern Galiuro Mountains, and expand the date of occurrence in this region as far back as the turn of the recent century.

Hopefully our expedition and these subsequent reports of Elegant Trogons will encourage previous visitors to the Galiuros to report their sightings and contribute to the overall knowledge of this ‘sky island’s’ avifauna. More importantly, we hope that our expedition will encourage future exploration of the bird life that occurs in this beautiful, rugged mountain range. Our observations and experiences during this trip will certainly inform future AZFO expeditions into the Galiuros, such as to investigate the aspen groves in the upper reaches of Douglas and Rattlesnake Canyons. The presence of Elegant Trogons in the Galiuro Mountains and Aravaipa Canyon will hopfeully result in expansion of the trogon censuses that have been conducted in the other southeastern Arizona ‘sky islands’ to this mountain range.

I want to thank John Barthelme, Sarah MacLean, Marceline VandeWater, and Nathan Williams for volunteering their time and expertise to making this amazing endeavor happen!

We hope you will join us for future AZFO expeditions!

LITERATURE CITED

Arizona Field Ornithologists. 2011. Spring 2011 seasonal report. Available from: http://azfo.org/seasonalReports/2011_spring.html#SoutheastAZ

Arizona Prescribed Fire Council. 2014. Tale of two fires—un-newsworthy fire is sign of success [Internet]. Available from: http://azprescribedfirecouncil.org/2014/07/24/tale-of-two- fires-un-newsworthy-fire-is-sign-of-success/

Brennan, T.C. and A.T. Holycross. 2006. A Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles in Arizona. Arizona Game & Fish Department: 150 p.

Corman, T.E., and C. Wise-Gervais. 2005. Arizona Breeding Bird Atlas. University of New Mexico Press. 636 p.

The Forest History Society. 2008. Guns and gold: history of the Galiuro Wilderness [Internet]. Available from: http://www.foresthistory.org/ASPNET/Publications/region/3/coronado/galiuro_wildernes s/contents.aspx

Inciweb. 2014. Final update: July 6 Oak Fire update [Internet]. Available from: http://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/article/3901/22230/

Monson, G., and A.R. Phillips. 1981. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Arizona, 2nd edition. University of Arizona Press. 240 p.

Phillips, A. R., Marshall, J., and G. Monson. 1964. The Birds of Arizona. University of Arizona Press, Tucson. 212 p.

Wakeling, B.F. 1998. Survival of Gould’s turkey transplanted into the Galiuro Mountains, Arizona. USDA Forest Service Wildlife Proceedings RMRS-P-5: 227-234.

Wetmore, A. 1935. The thick-billed parrot in southern Arizona. Condor 37:18-21.

APPENDIX

Table 1. Total numbers for the 114 species detected for the eastern Galiuro Mountains and adjacent foothills and grasslands of the northern Sulphur Springs Valley on May 1-3, 2015.

|

|

|

|

©2010 |

HOME | | | REPORT SIGHTINGS | | | PHOTOS | | | BIRDING | | | JOURNAL | | | ABOUT US | | | CHECKLISTS | | | AZ BIRD COMMITTEE | | | EVENTS | | | LINKS |